Growing up in twenty-first-century Britain, I was often struck by a feeling of anomie. Around the time I was born, John Major tried to evoke a vanished past by conjuring “long shadows on county grounds” and “old maids bicycling to Holy Communion through the morning mist.” As for my generation, it had only the faintest notion of our once-great national religion. The Anglican Church had become a shadow of itself, reduced to the picturesque, empty buildings that adorned our lanes and streets. It was a shadow we noticed when we shuffled into the parish church’s cold, echoing interior for the Harvest Festival and sang the cheery modern hymns that church bureaucrats imagined we would like.

Anomie was one thing; the ferocious renunciation of tradition I encountered at university was quite another. I had hoped that the spiritual emptiness of wider society was a result of ignorance, and that the academy—especially the ancient, venerable, Gothic academy of Oxford—had preserved what I vaguely imagined was my country’s noble heritage. Studying philosophy did provide some engagement with an intellectual inheritance, but for anyone moderately interested in public life, the campus movements for “social justice” were impossible to ignore. All of these—whether their goal was the liberation of women, of LGBT persons, or of ethnic minorities—seemed to have the same vision of man: a deracinated, protean aggregate of desires. These movements gained in strength every year. Formerly apolitical spaces were distorted by the need to appease one demand after another. The culture of the university, once imbued with the brash boyishness of the English public schools, now accommodated the sterile, strenuous inclusivity of progressive zealots.

After three years of this, I was frustrated and alienated. I needed a purpose. Philosophy classes had sharpened my inquiries, but they didn’t rectify the meaninglessness all around me. My utopian peers found their purpose in crusades against racism and homophobia, but their contempt for England revolted me. I chose a different course and embarked on a search for God.

Where could a lost soul go? Nowhere in college or country offered an answer. What the campus Conservative Party outlined was absurd: We can pick up the fragments of our culture by putting on three-piece suits, getting riotously drunk, and reviving the divine right of kings. I had plenty of opportunities to engage with orthodox Christians, and I sincerely wanted Christianity to be true. It was clear to me that what the authorities in my world celebrated—the collapse of family life, the slaughter of the unborn, the deterioration of high culture—were, in truth, social evils that followed from the decline of the Church. Christianity seemed the natural alternative to secularity.

But when I entered the chapels and listened to the ministers, the regeneration I sought didn’t happen. Christian voices sounded all too agreeable and compromising. I wanted something stronger, something that didn’t bargain with secularism. I found it in Islam.

The first part of the Islamic shahada, or testimony of faith, is la ilaha il’Allah, “there is no god but God”—an uncompromising statement of pure monotheism. Islam puts the One God front and center, a simple and commanding being. Philosophy had persuaded me that God was an intellectual and moral necessity. I did not know whether his existence could strictly be proven, but I recognized the dishonesty and intellectual contortions atheism required. Without an absolute, transcendent Lord, I could see no way to objective morality and to a purpose and order in the cosmos that could overcome the transience of this world. I doubted that we could justify even belief in causal regularities without a constantly acting Creator to guarantee them. If I were to embrace God, then God would need to be an unmediated, undifferentiated, and decisive Omnipotence, whom I might willingly obey.

My problem with Christianity arose from the contrast between the abstract Divinity who answers such questions and the all-too-human majesty of Jesus (peace be upon him). Surely God, if he was God, had to be a perfectly simple being, absolutely distinct from his creation. If his separation was questioned, then he wasn’t really the infinite Creator I sought. How could this transcendent being be identical with the fleshy Messiah portrayed in church, complete with his bloody stigmata? The mystery of the Trinity seemed to me a dark glass that made God’s majesty dimmer, not brighter. Rather than puzzling indefinitely, I sided with simplicity and affirmed the Islamic doctrine of tawhid: God’s absolute oneness.

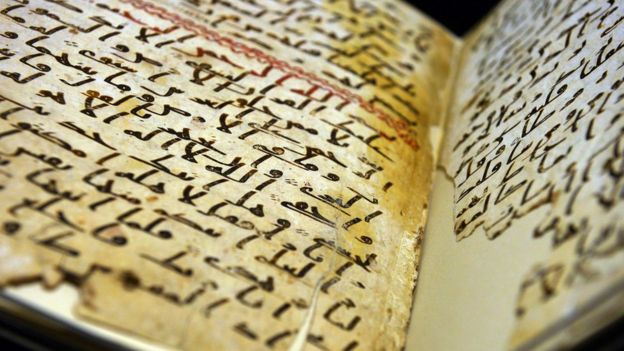

So goes the first shahada. The second declares Muhammadun rasool’Allah: “Muhammad is the Messenger of God.” This is a matter of Scripture. In the Qur’an’s claims to be the direct speech of God, Islam again seemed a simpler and more compelling story. One God, one final Message.

C. S. Lewis argued that a man claiming to be God must be either a lunatic, a liar, or truly the Lord. Likewise, a man claiming to be a Messenger of God must be either insane, dishonest, or just what he says he is. I judged, based on my reading of history, that Muhammad (peace be upon him) could not have been either of the former two. The facts of his life and ministry reveal an honest man in full possession of his rational faculties. By contrast, it wasn’t hard for me to avoid Lewis’s trilemma, because Muslims simply do not believe that Jesus (peace be upon him) ever claimed to be God. Rather, we hold him to have been another prophet like Moses, Abraham, and Isaac (peace be upon them all). The final piece of the puzzle fell into place upon my learning of the long process of redaction and recomposition that produced the canon that became the Bible. This was consistent with the Islamic narrative of an earlier revelation that, though true, was imperfectly preserved. The Qur’an was the unification and confirmation of what the Bible merely tried to assemble.

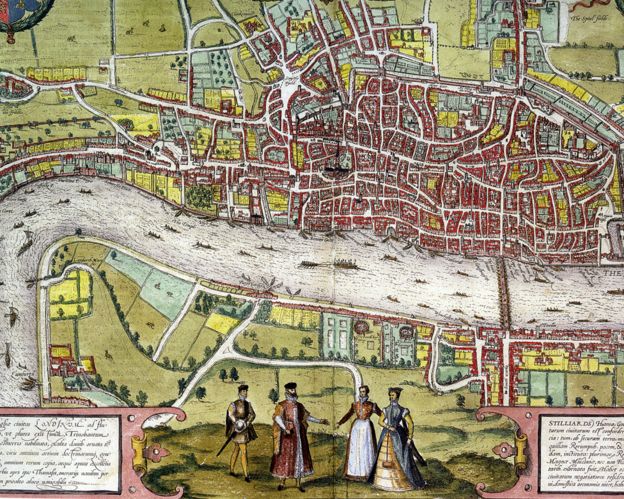

All reasoning is motivated by something—and perhaps, under different circumstances, I might have reached different conclusions. But what started my search for God was my inability to feel at home in the England of the 2010s. The country in which I was born, raised, and schooled had imparted the sense of Islam as wholly foreign, strange, and backward, the antithesis of our entire civilization. And as a historical matter, I had learned, the West emerged in part through its self-definition over against Islam. This, then, was the hardest part: opening my heart to the truth of Islam and ceasing to see it as another destabilizing force, alien to the tradition I loved.

What was happening around me made it easier, however. At one point, a campaign was launched at my university called, “Why is my curriculum white?” The premise was that a British university should not teach British authors because doing so might make cultural minorities feel unwelcome. In other words, “Orientalism,” which cast the East as Other, had to stop. On hearing of this campaign, I recognized that the only way to create a world with no “others” is to have no self. While my Christian conservative friends objected to this denigration of the West, I saw the deeper aim, which was to eliminate the self, to deny all of us a home, a country, and indeed a religion. I had absorbed enough of the remnants of what Charles Taylor calls the British synthesis—the conflation of Britishness, Christianity, liberty, and sexual restraint—to experience such losses as catastrophic. My journey toward Islam thus began not with a rejection of the Western tradition and inheritance but with a strong desire to affirm as much of it as might prove compatible with religious truth. Faith, I hoped, could be reconciled with the secondary loves of my family and flag.

Of course, Islam, like all universalist religions, abhors narrow, jingoistic nationalism and ethnocentrism. But it respects the deeper patriotic impulse that originates in love of one’s home. This point was made clear to me by Roger Scruton’s England: An Elegy. English culture and institutions, Scruton argues, were founded on a deep connection with geographical particularity and manifested in forms such as the horizontal idiom of English church architecture, which affirms an enchantment in the land rather than gesturing dizzyingly (and futilely) upward. Islam, I was happy to discover, values this type of organic connection to place while treating patriotic attachment to the nation-state as a flawed loyalty. The Qur’an rejects nationalistic chauvinism while nonetheless recognizing that mankind is divided into “nations and tribes” for which we naturally have affection.

So, I began to see that Islam was able to appreciate the West’s good qualities. As I studied further, I saw the possibility of beneficial exchange between these historically opposed cultures. I learned how much Islamic civilization owes to Greek philosophy, Roman statecraft, and now the Industrial Revolution. By coming to see Islam as a means of stability and regeneration, I overcame the difficulty of adopting a religion other than that of my fathers. My peers and teachers were busy desecrating the Western tradition. Islam stood a chance of preserving it.

By this time, Islam felt more familiar to me than did the Christianity of my home. Tepid, half-believing Anglicanism—“almost-instinct almost true,” in Philip Larkin’s words—couldn’t stop the spread of utopian progressivism on campus or London’s arid diversity. I needed a different antidote for the hedonism of my culture. By the time I went to North Africa to witness Islam as a lived reality, my anxieties had dissolved. I was soon able to enter the state of islam, or “submission to God,” without ceasing to be the person I had been. I did not change my name, my style of dress, or my diet (save that I now take halal beef with my eggs rather than bacon). I enjoy the Anglo-Muslim poetry and music produced by my coreligionists over the last century and a half. I am still moved by the landscapes of Constable and I still feel that Shakespeare offers among the deepest insights of any writer into the vicissitudes of the human soul. Above all, the vapid global consumer monoculture dissipates when I undergo submission to the One True God. I appreciate the best of the West, not despite being a Muslim, but because of it.

I experience being Muslim and being British not as tension, but as convergence. As the Islamic scholar Umar Faruq Abd-Allah puts it, Islam is the clear water of pure monotheism, colored by the bedrock of the native soil over which it flows. Life as a Muslim in the West does not consign you to being a diasporic Arab or Desi; it need not produce awkward and anxious suspension between two civilizations. Another scholar, Timothy Winter, sums up my feelings eloquently: “[Islam] is generous and inclusive. It allows us to celebrate our particularity, the genius of our heritage; within, rather than in tension with, the greater and more lasting fellowship of faith.” It is my ardent hope that the cause of God and truth will be served when others, too, come to see this.

Jacob Williams is a writer living in London, England.

https://www.firstthings.com/article/2019/05/why-i-became-muslim